When supply chain failure makes delivery impossible, your contract is not a death sentence—it is your primary tool for strategic risk management in Canada.

- The key is not finding a single escape clause, but building a “defensibility architecture” that proves you have taken all reasonable steps to perform.

- Canadian courts apply a high standard; concepts like “force majeure” and “frustration” are narrowly interpreted and require more than mere economic hardship to invoke.

Recommendation: Immediately begin documenting every action taken to mitigate the disruption. This evidence is the foundation of your negotiating power and legal defence.

As a manufacturing director, it’s the scenario that keeps you up at night. The call comes in: a critical raw material supplier cannot deliver, indefinitely. Suddenly, your own production lines are at risk, and your ability to fulfil customer orders is in jeopardy. Your contractual obligations, once a standard part of business, now feel like a tightening vise. In this moment of crisis, the common advice is often to find an exit—check the force majeure clause, declare the contract impossible to perform, and hope for the best.

But this reactive approach is a high-stakes gamble. Relying on a single clause ignores the nuanced reality of Canadian commercial law. What if the disruption is a cyberattack on your supplier? What if your costs have just tripled, but performance is still technically possible? The true path to navigating this crisis lies not in finding one escape hatch, but in proactively building a robust legal position. It requires a shift in mindset: your contract is not a rigid trap, but a dynamic toolkit for negotiation and risk management.

This approach involves constructing what can be termed a ‘defensibility architecture’—a systematic framework of proof, precise communication, and a clear-eyed understanding of your legal leverage points. By doing so, you transform a moment of potential breach into an opportunity to control the narrative, manage your counterparties’ expectations, and protect your business from catastrophic liability. It’s about turning legal theory into a practical, problem-solving strategy.

This guide provides a strategic breakdown of the key legal concepts and contractual levers at your disposal. We will examine the critical distinctions that can make or break your case, from the wording of your commitments to the steps you must take when a partner signals distress. Understanding these elements is the first step toward regaining control when your supply chain fails.

Summary: Managing Contractual Duties in a Disrupted Supply Chain

- Means vs Result: Why Committing to “Best Efforts” is Safer Than “Guaranteed Delivery”?

- Is a Cyberattack a “Force Majeure” Event That Excuses Your Commercial Obligations?

- Joint and Several Liability: Why You Might Pay Your Partner’s Share of the Debt?

- The “Frustration” Doctrine: When Can You Walk Away Because the Deal Make No Sense Anymore?

- Time is of the Essence: Why Missing a Deadline by 1 Hour Can Kill the Deal?

- Why Does a “Perfected” Security Interest Beat a General Creditor in 99% of Bankruptcies?

- What to Do When a Supplier Says They “Might Not” Deliver Next Month?

- How to Negotiate a Limitation of Liability Clause That Won’t Bankrupt Your Agency?

Means vs Result: Why Committing to “Best Efforts” is Safer Than “Guaranteed Delivery”?

In the world of commercial contracts, the difference between promising to *achieve* a result and promising to *try* to achieve it is monumental. An “obligation of result” (e.g., “guaranteed delivery by June 1st”) is absolute. If the result isn’t met, you are in breach, regardless of the cause. Conversely, an “obligation of means” (e.g., using “best efforts” or “commercially reasonable efforts”) requires you to demonstrate a rigorous process, not a perfect outcome. This distinction is your first line of defence in a supply chain crisis.

When you’ve committed to “best efforts,” the focus shifts from the failure to deliver to the quality of your attempts to do so. But what does “best efforts” actually mean under Canadian law? It is a stringent standard. As the British Columbia Supreme Court has clarified, it involves more than just a good try. As Justice Dorgan stated in a landmark case:

In Atmospheric Diving Systems Inc v International Hard Suits Inc, the British Columbia Supreme Court established that ‘best efforts’ means taking, in good faith, all reasonable steps to achieve the objective, carrying the process to its logical conclusion and leaving no stone unturned.

– Justice Dorgan, Atmospheric Diving Systems Inc v International Hard Suits Inc (1994)

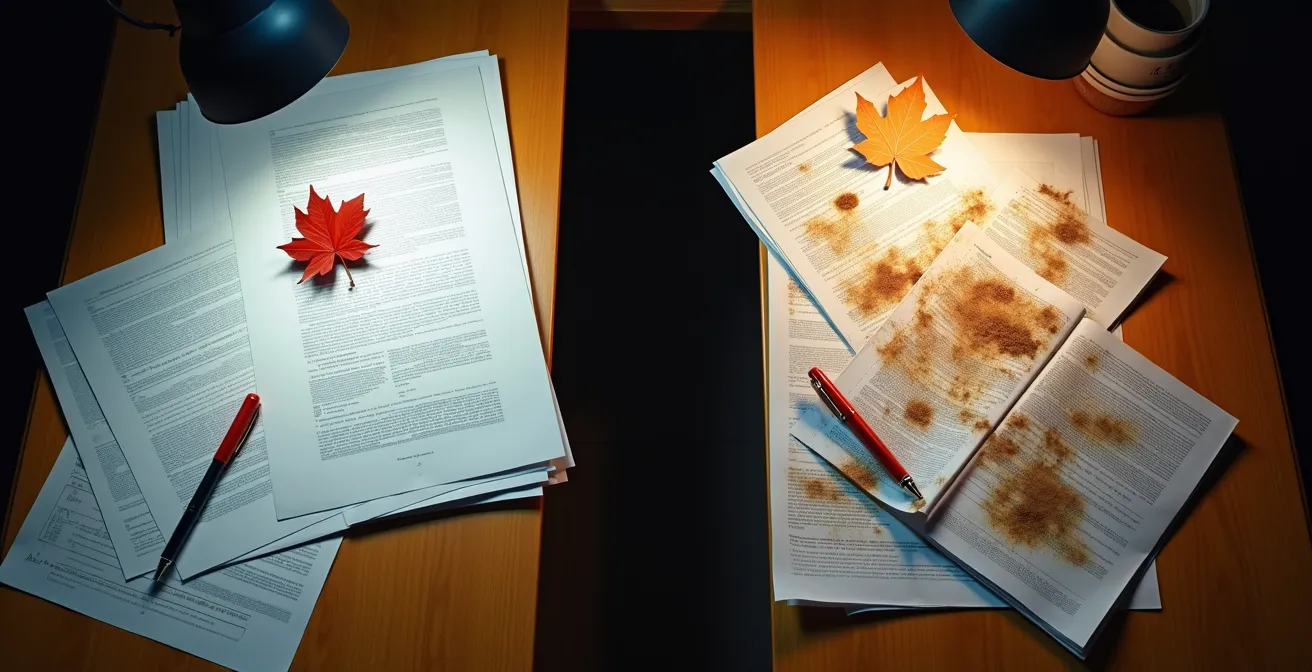

This means you must build a comprehensive “defensibility architecture” of evidence. Your goal is to create an irrefutable record that you exhausted all viable options. This documentation isn’t just for a potential court case; it is a powerful negotiating tool to demonstrate your commitment to your counterparty and justify a non-punitive resolution. The key is to document everything, transforming your crisis management activities into a body of proof.

The visual of meticulously organized files is more than just an aesthetic; it represents the structured approach required. Every email, every meeting minute, and every cost analysis of an alternative becomes a brick in your defensive wall. To succeed, your documentation must be contemporaneous, detailed, and aimed at proving you left no stone unturned in your quest to perform.

Your Action Plan: Building a “Best Efforts” Defence in Canada

- Document all alternative supplier searches with timestamps and correspondence records.

- Maintain crisis meeting minutes showing decision-making processes and efforts undertaken.

- Keep formal communications with all stakeholders explaining steps taken to fulfill obligations.

- Record cost analyses of alternative solutions considered, even if deemed uneconomical.

- Preserve evidence of consultations with industry experts or legal counsel.

- Archive all attempts to mitigate damages or find workarounds, successful or not.

Is a Cyberattack a “Force Majeure” Event That Excuses Your Commercial Obligations?

When an unforeseen event makes performance impossible, many directors immediately look to the “force majeure” clause. This contractual provision is designed to excuse a party from its obligations when an extraordinary event, beyond its control, occurs. Classic examples include natural disasters (“acts of God”), war, or government action. However, the modern supply chain faces newer threats, like cyberattacks, raising a critical question: does a ransomware attack on your supplier count as force majeure?

The answer in Canada is: it depends entirely on the wording of your contract. There is no common law right to claim force majeure; the right exists only if it is explicitly included in your agreement. Furthermore, for an event to qualify, it must be specifically listed or fall under a general “catch-all” phrase. A generic clause mentioning “any event beyond the parties’ reasonable control” might be arguable, but a specific clause that explicitly lists “cyberattacks,” “data breaches,” or “malicious software” provides a much stronger position. Without such precise language, you may be left without an excuse.

The impact of supply chain disruptions is significant, forcing many businesses to pass on costs. Indeed, a 2022 survey found that 66% of Canadian business leaders have had to increase the prices of their products due to rising input costs. While this highlights the widespread nature of the problem, economic hardship alone is not a force majeure event. The event must typically make performance impossible, not just more expensive.

Ultimately, Canadian courts interpret force majeure clauses narrowly. As legal experts point out, the right to be excused from performance due to unforeseen events requires an express clause. If your contract is silent on the matter, or if the specific event (like a cyberattack) is not covered, you cannot rely on force majeure. Your only remaining option would be the much more difficult doctrine of frustration, which requires the event to render the entire purpose of the contract impossible to achieve.

Joint and Several Liability: Why You Might Pay Your Partner’s Share of the Debt?

Supply chain disruptions often reveal risks not just with external suppliers, but also with your own business partners. If you’ve entered into a joint venture or partnership to deliver a product or service, the default legal structure could expose you to significant financial danger. The concept you must understand is joint and several liability, a cornerstone of Canadian partnership law. In simple terms, it means that if a debt is owed by the partnership, the creditor can pursue any single partner for the *entire* amount, not just their proportional share.

Imagine your joint venture fails to deliver an order due to a default by your partner. The client can sue you for 100% of the damages, leaving you to try and recover your partner’s share from them later—a difficult task if they are financially insolvent. This risk is not theoretical; it is the default reality for general partnerships. Your personal and corporate assets could be at stake to cover a failure that wasn’t even your fault. This makes the choice of legal structure for any collaboration a critical risk management decision.

Fortunately, there are ways to structure collaborations to shield yourself from this exposure. Incorporating a joint venture creates a separate legal entity, and liability is generally limited to the assets held by that corporation. This “corporate veil” is a powerful protection. The choice of structure depends on the project’s scale, risk profile, and the relationship between the partners.

The following table provides a simplified overview of common collaborative structures in Canada and their corresponding liability exposure. Understanding these differences is essential before entering into any new partnership agreement.

| Structure Type | Liability Exposure | Protection Level | Common in Canada |

|---|---|---|---|

| General Partnership | Full joint and several liability | No protection – partners personally liable | Small businesses, professional firms |

| Limited Partnership | Limited partners protected, general partner exposed | Partial protection based on role | Real estate, investment funds |

| Incorporated Joint Venture | Limited to corporate assets | Corporate veil protection | Major projects, construction |

| Contractual Joint Venture | As specified in agreement | Varies by contract terms | Resource extraction, technology |

The “Frustration” Doctrine: When Can You Walk Away Because the Deal Make No Sense Anymore?

What happens when an event is so catastrophic and unforeseen that it doesn’t just make your contract difficult, but renders its entire purpose meaningless? This is where the common law doctrine of frustration comes into play. Unlike force majeure, which depends on a specific clause in your contract, frustration is a legal remedy a court can apply to terminate a contract when a supervening event makes performance radically different from what was originally agreed upon.

However, as a director in a crisis, you must understand that the bar for proving frustration in Canada is exceptionally high. It is not enough for performance to become more expensive, more difficult, or even unprofitable. The event must fundamentally destroy the commercial purpose of the agreement. For instance, if you contracted to renovate a specific building and that building burns down, the contract is likely frustrated. But if your raw material costs double due to a supplier issue, making your project a money-loser, courts will almost certainly say that is a business risk you assumed.

This is a critical point that business leaders often misunderstand. As legal expert Seema Lal of Singleton Urquhart Reynolds Vogel LLP notes, relying on frustration is a last resort, not a first-line strategy.

In Canadian common law, the right to be excused from performance based on extraordinary events does not exist without an express force majeure clause. The only exception is if the event renders the contract impossible to perform, allowing a party to seek a declaration that the contract has been legally frustrated.

– Seema Lal, Partner at Singleton Urquhart Reynolds Vogel LLP, ReNew Canada Magazine

The doctrine essentially acknowledges that the contract has been shattered beyond repair by an outside event, creating a chasm between the original agreement and the current reality. It effectively ends the contract at the moment of the frustrating event, relieving both parties of future obligations.

Because the threshold is so high, you should never assume an event will lead to frustration. The wiser strategy is always to focus first on the explicit terms of your contract, your “best efforts” obligations, and your duty to mitigate damages. Viewing frustration as an unlikely escape hatch reinforces the importance of building a solid ‘defensibility architecture’ based on the tangible evidence of your actions.

Time is of the Essence: Why Missing a Deadline by 1 Hour Can Kill the Deal?

In many commercial agreements, deadlines are treated as important targets. A slight delay may be tolerated or result in minor penalties. However, when a contract includes the phrase “time is of the essence,” the legal landscape changes dramatically. This short, powerful clause elevates every deadline from a guideline to an essential condition of the contract. Missing a “time is of the essence” deadline, even by a small margin, can give the other party the right to terminate the entire agreement and sue for damages.

As a manufacturing director managing a disrupted supply chain, you must be acutely aware of which of your contracts contain this clause. If your own delivery is contingent on a supplier’s performance, and your client contract states that time is of the essence, you are in a high-risk position. A delay from your supplier could have a cascading effect, leading to a material breach of your own obligations and potentially catastrophic financial consequences for your company.

The enforceability of this clause is not theoretical. Canadian courts regularly uphold it, especially in industries where timing is critical. A prime example is commercial real estate. In fast-moving markets like Toronto or Vancouver, a delay of even an hour in a competitive bidding situation can be grounds for termination. The court considers not just the contract’s language but also the commercial context. A delay that might be forgiven in a slow-moving project could be fatal in a high-velocity transaction where market conditions can change in an instant.

If you are the one facing a delay from a counterparty, this clause can also be used as a powerful tool. If a supplier is late and your contract does not already state that time is of the essence, you can often issue a formal “Notice to Complete.” This notice sets a new, reasonable deadline and explicitly states that time is *now* of the essence. If the supplier misses this new deadline, you have manufactured a clear legal basis to terminate the contract and pursue other options. This is a strategic move that requires careful execution and legal guidance to be effective.

Why Does a “Perfected” Security Interest Beat a General Creditor in 99% of Bankruptcies?

In a worst-case scenario where a key supplier or customer goes bankrupt, your ability to recover money or assets depends on a crucial legal distinction: are you a secured creditor or a general (unsecured) creditor? A secured creditor is someone who has a “security interest” in a specific asset of the debtor, such as inventory or equipment. A “perfected” security interest is one that has been properly registered with the correct provincial authority, putting the world on notice of your claim. This simple act of registration elevates you to the front of the line for repayment.

When a company becomes insolvent, its assets are liquidated to pay off debts. Secured creditors with perfected interests get paid first from the proceeds of the assets they have a claim against. General creditors, such as suppliers who sold goods on an open account, are lumped together and only get paid from whatever is left over—which is often little to nothing. In 99% of cases, having a perfected security interest means you recover at least some of your money, while being a general creditor often means a total loss.

For a manufacturing director, this has two critical implications. First, when extending credit to a customer, you should consider taking a security interest in the goods you are selling via a Purchase Money Security Interest (PMSI). This ensures that if the customer goes bankrupt, you have a priority claim to get your goods back or be paid from their sale. Second, you must understand that your lenders (like banks) almost certainly have a perfected security interest over all your assets. This gives them immense power if you default on your obligations.

Registering a security interest in Canada is a provincial matter, governed by Personal Property Security Act (PPSA) legislation in most provinces and the Civil Code in Quebec. The process is straightforward but must be done correctly. The table below outlines the primary registry systems in key Canadian provinces.

| Province | Registry System | Registration Time | Search Cost |

|---|---|---|---|

| Ontario | PPSA Registry | Immediate online | $8-12 per search |

| Quebec | RDPRM | 1-2 business days | $3-15 per search |

| Alberta | PPSA Registry | Immediate online | $10-15 per search |

| British Columbia | PPSA Registry | Immediate online | $7-10 per search |

What to Do When a Supplier Says They “Might Not” Deliver Next Month?

One of the most challenging situations in supply chain management is not an outright failure, but a warning signal. A supplier calls and says they are facing challenges and “might not” be able to deliver your next shipment. This ambiguous statement puts you in a difficult strategic position. If you wait and they fail to deliver, your own production could halt. If you overreact and immediately source a new supplier, you might be in breach of contract if the original supplier manages to perform after all.

This scenario triggers a legal concept known as anticipatory breach or repudiation. This occurs when one party indicates, by words or actions, that they will not be performing their future obligations. Under Canadian common law, this gives the non-breaching party (you) a critical choice. As outlined in a legal analysis of international supply chain disputes, you have two main paths. You can either (1) accept the repudiation, treat the contract as terminated immediately, and sue for damages, or (2) affirm the contract, demand performance, and wait to see if they actually breach.

Each path carries risks. Accepting the repudiation is risky because if a court later decides the supplier’s statement wasn’t a clear enough refusal to perform, *you* could be the one found in breach for terminating prematurely. Affirming the contract keeps the deal alive but leaves you in a state of uncertainty. The most strategic response, therefore, is often a middle ground. You should not immediately terminate. Instead, you should send a formal written demand for “adequate assurance of performance.”

This formal request puts the onus back on the supplier. You can state that their communication has given you reasonable grounds for insecurity and that you require a clear, written commitment within a short timeframe (e.g., 48-72 hours) that they will perform as agreed. Their response—or lack thereof—will provide a much clearer legal basis for your next move. If they provide assurance, you can hold them to it. If they fail to do so, their failure strengthens your case that they have repudiated the contract, making it much safer for you to terminate and seek alternatives.

Key Takeaways

- Your primary goal is not to escape a contract, but to build a “defensibility architecture” of evidence proving your reasonable efforts.

- “Force majeure” and “frustration” are high legal bars in Canada; they are not easy escapes for economic hardship. Your contract’s specific wording is paramount.

- Proactive documentation and formal communication (like a demand for assurance) are your most powerful tools for negotiation and risk mitigation.

How to Negotiate a Limitation of Liability Clause That Won’t Bankrupt Your Agency?

While managing a current crisis is paramount, a true strategic approach involves looking ahead to prevent future disasters. One of the most critical, yet often overlooked, tools for this is the Limitation of Liability (LoL) clause. This provision sets a cap on the amount of damages one party can claim from another in the event of a breach. For a manufacturing director, negotiating a reasonable LoL clause in both your customer and supplier contracts is a fundamental act of corporate self-preservation. Without it, your potential liability could be unlimited, exposing your business to existential risk from a single failure.

A well-drafted LoL clause does not absolve you of all responsibility. Instead, it creates a predictable and insurable level of risk. The key is to negotiate a cap that is commercially reasonable for both parties. A common approach is to cap direct damages at the total value of the contract or the fees paid over a specific period (e.g., 12 months). This ties the risk directly to the economic value of the relationship.

Equally important is the exclusion of certain types of damages. It is standard practice in Canada to negotiate for the exclusion of indirect or consequential damages. These are damages that don’t flow directly from the breach, such as lost profits, loss of business reputation, or damages your customer has to pay to *their* customers. These can be unpredictable and far exceed the value of your contract, so excluding them is a vital protection. However, courts will not allow you to exclude liability for everything, particularly for gross negligence, willful misconduct, or fraud.

The following table outlines common strategies for capping different types of damages in Canadian B2B contracts, providing a framework for your next negotiation.

| Damage Type | Typical Cap | Enforceability in Canada | Common Exclusions |

|---|---|---|---|

| Direct Damages | Contract value or 12 months fees | Generally enforceable | Gross negligence, willful misconduct |

| Indirect/Consequential | Often fully excluded | Usually upheld if reasonable | Personal injury, IP infringement |

| Liquidated Damages | Specified amount/formula | Must be genuine pre-estimate | Fraud, criminal acts |

| Service Credits | 5-30% of monthly fees | Highly enforceable | Data breaches, confidentiality |

To effectively apply these legal concepts, the next logical step is a strategic review of your current commercial agreements to identify both risks and leverage points before the next crisis hits.